Speeding up Python 147x with Cython

When evaluating Python for enterprise projects, the concern over its ultimate speed arises from time to time. Of course, fundamental speed-up comes only from a better algorithm or better approach to the problem at hand. However, on the programming language level, Python is indeed lacking in ultimate speed due to many, many hoops in service of its nature as a very high-level and dynamic language.

There are a number of ways to diminish this problem. Three primary ways are

- Call an existing C/C++ library for speed-critical tasks.

- Implement speed-critical tasks in C/C++, as part of the Python project.

- Implement speed-critical tasks in Cython, as part of the Python project.

The first approach assumes the existence of a third-party library (which could be authored by the owner of the Python project in question, but conceptually is an external library). The second and third approaches are under the control of the Python developer, hence amenable to experimentation and refactoring. The first two approaches rely on Python’s C API, either the “raw” API or some higher level wrapper. The third approach does not require the developer to directly deal with the C API.

In this post I will showcase the third approach. Specifically, I will speed-tune a very simple function through a number of phases, first within pure Python but ultimately using Cython. The main objective of the post is to demonstrate the ease and potential benefit of Cython to total newbies.

Set it up

Below is the function we need to speed up. Given a UNIX timestamp, the function returns the week-day, a number between 1 and 7 inclusive. Suppose in a real-world project we need to call this function a large number of times, and the time spent on this function has proven to be considerable.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

# file 'version01.py'.

from datetime import datetime

def weekday(ts):

dt = datetime.utcfromtimestamp(ts)

wd = dt.isoweekday()

return wd

def weekdays(ts):

return [weekday(t) for t in ts]

We have created a Python package named pycc and made it visible on PYTHONPATH. The above is the module version01 in this package. We also created a utility module profiler in package pycc with the content as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

# profiler.py

import time

from functools import wraps

import line_profiler

def timed(func):

@wraps(func)

def profiled_func(*args, **kwargs):

time0 = time.perf_counter()

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

time1 = time.perf_counter()

print('')

print('Function `', func.__name__, '` took ', time1 - time0, 'seconds to finish')

print('')

return result

return profiled_func

def lineprofiled(*funcs):

"""

A line-profiling decorator.

Args:

funcs: functions (function objects, not function names) to be line-profiled.

If no function is specified, the function being decorated is profiled.

Example:

@lineprofiled()

def myfunc(a, b):

g(a)

f(b)

@lineprofiled(g, f)

def yourfunc(a, b):

x = g(a)

y = f(b)

s(x, y)

"""

def mydecorator(func):

nonlocal funcs

if not funcs:

funcs = [func]

@wraps(func)

def profiled_func(*args, **kwargs):

func_names = [f.__name__ for f in funcs]

profile = line_profiler.LineProfiler(*funcs)

z = profile.runcall(func, *args, **kwargs)

profile.print_stats()

stats = profile.get_stats()

if not stats.timings:

warnings.warn("No profile stats.")

return z

for key, timings in stats.timings.items():

if key[-1] in func_names:

if len(timings) > 0:

func_names.remove(key[-1])

if not func_names:

break

if func_names:

# Force warnings.warn() to omit the source code line in the message

formatwarning_orig = warnings.formatwarning

warnings.formatwarning = lambda message, category, filename, lineno, line=None: \

formatwarning_orig(message, category, filename, lineno, line='')

warnings.warn("No profile stats for %s." % str(func_names))

# Restore warning formatting.

warnings.formatwarning = formatwarning_orig

return z

return profiled_func

return mydecorator

version01 is our very baseline version.

The function weekdays is our “entry point” for testing. The testing code is as follows.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

# test1.py

from pycc import version01 as mymod

from pycc.profiler import timed

@timed

def do_them(timestamps):

fn = mymod.weekdays

return fn(timestamps)

if __name__ == "__main__":

n = 1000000

timestamps = [i * 1000 for i in range(n)]

z = do_them(timestamps)

The decorator timed prints the execution time of the function that is decorated by it.

Running it, we get the execution time of version01:

1

2

3

$ python test1.py

Function ` do_them ` took 0.8810409489960875 seconds to finish

Later we will adapt test1.py to time other versions, and will simply rename the script according to the version, e.g. test2.py, but will not show the slightly adapted testing code.

Make it faster

version01 is clean and clear. However, when we think hard about the speed, we realize that figuring out the week-day from a timestamp involves quite a few steps of arithmetic. We could improve the speed by doing the time difference from a reference timestamp, for which we know the week-day. This could work because, unlike date, week proceeds strictly regularly.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

# file 'version02.py'.

from datetime import datetime

import pytz

class TimestampShifter:

DAY_SECONDS = 86400

WEEK_SECONDS = 604800

def __init__(self):

basedate = datetime.now(pytz.timezone('utc'))

self._weekday = basedate.isoweekday() # Monday is 1, Sunday is 7

dt = basedate.replace(hour=0, minute=0, second=0, microsecond=0)

self._timestamp = int(dt.timestamp())

def shift_to(self, ts):

ts_delta = ts - self._timestamp

if ts_delta < 0:

ts_delta += ((-ts_delta) // self.WEEK_SECONDS + 1) * self.WEEK_SECONDS

td = ts_delta % self.WEEK_SECONDS

nday = td // self.DAY_SECONDS

weekday = self._weekday + int(nday)

if weekday > 7:

weekday = weekday - 7

return weekday

def weekday(ts):

shifter = TimestampShifter()

z = shifter.shift_to(ts)

return z

def weekdays(ts):

shifter = TimestampShifter()

return [shifter.shift_to(t) for t in ts]

Time it:

1

2

3

$ python test2.py

Function ` do_them ` took 0.9040505230077542 seconds to finish

Sorry, not faster than the baseline version. Before working on the speed, let’s verify the result is correct by adding a function to verify results against the baseline:

1

2

3

4

5

6

# file 'version01.py', continued:

def verify(timestamps, results):

for x, y in zip(timestamps, results):

yy = weekday(x)

assert y == yy

Let me just report that all later versions have passed this check.

Now on to speed tuning.

In version02, we create the reference time by querying the current time at object initiation. Upon rethinking, it becomes clear that we don’t need to query any ‘current’ time—we just need to use a fixed and convenient reference time.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

# file 'version03.py'.

def weekday(ts):

ts0 = 1489363200 # 2017-03-13 0:0:0 UTC, Monday

weekday0 = 1 # ISO weekday: Monday is 1, Sunday is 7

DAY_SECONDS = 86400

WEEK_SECONDS = 604800

ts_delta = ts - ts0

if ts_delta < 0:

ts_delta += ((-ts_delta) // WEEK_SECONDS + 1) * WEEK_SECONDS

td = ts_delta % WEEK_SECONDS

nday = td // DAY_SECONDS

weekday = weekday0 + nday

if weekday > 7:

weekday = weekday - 7

return weekday

def weekdays(ts):

return [weekday(t) for t in ts]

Time it:

1

2

3

$ python test3.py

Function ` do_them ` took 0.5782521039946005 seconds to finish

A speed-up from 0.88 to 0.58 seconds. Modest but real.

And faster

Make a copy of version03.py and call the new file version04.pyx. Make no change whatsoever to the actual code. The pyx extension indicates it’s a Cython source file.

Compile it using the Python package easycython:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

$ easycython version04.pyx

Warning: Extension name 'version04' does not match fully qualified name 'pycc.version04' of 'version04.pyx'

Compiling version04.pyx because it changed.

[1/1] Cythonizing version04.pyx

running build_ext

building 'version04' extension

creating build

creating build/temp.linux-x86_64-3.5

gcc -pthread -Wno-unused-result -Wsign-compare -DNDEBUG -g -fwrapv -O3 -Wall -Wstrict-prototypes -fPIC -I/usr/local/lib/python3.5/site-packages/numpy/core/include -I/usr/local/include/python3.5m -c version04.c -o build/temp.linux-x86_64-3.5/version04.o -O2 -march=native

gcc -pthread -shared build/temp.linux-x86_64-3.5/version04.o -L/usr/local/lib -lpython3.5m -o /home/docker-user/work/src/pycctalk/pycc/version04.cpython-35m-x86_64-linux-gnu.so

This creates file version04.c, which is a C translation of the Cython source code. The C source is then compiled into a dynamic library, named with extension so.

1

2

3

4

$ ls

__init__.py build/ version03.py version04.html

__pycache__/ version01.py version04.c version04.pyx

_cc11binds.cc version02.py version04.cpython-35m-x86_64-linux-gnu.so*

After this point, version04 can be used just like any regular Python module. Let’s time it:

1

2

3

$ python test4.py

Function ` do_them ` took 0.29948758000682574 seconds to finish

Simply handing version03 off to Cython without code change has led to a speed-up from 0.58 to 0.30 seconds. Not huge, but significant.

In general, one should not expect huge performance gains by simply compiling with Cython. The recommended approach is to stay in pure Python as much as one can, identify speed bottlenecks, turning the bottleneck operations into Cython, and further tune the (short) Cython code.

And faster

Cython is a Python compiler that understands static type declarations and use them to generat C code. The first rule of using Cython is basically the following:

As long as you know a variable is a simple C type such as int and float, declare it.

Variable types are declared via the cdef keyword. Argument types are declared in the C function style.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

# file 'version05.pyx'.

def weekday(long ts):

cdef long ts0, weekday0, DAY_SECONDS, WEEK_SECONDS

cdef long ts_delta, td, nday, weekday

ts0 = 1489363200 # 2017-03-13 0:0:0 UTC, Monday

weekday0 = 1 # ISO weekday: Monday is 1, Sunday is 7

DAY_SECONDS = 86400

WEEK_SECONDS = 604800

ts_delta = ts - ts0

if ts_delta < 0:

ts_delta += ((-ts_delta) // WEEK_SECONDS + 1) * WEEK_SECONDS

td = ts_delta % WEEK_SECONDS

nday = td // DAY_SECONDS

weekday = weekday0 + nday

if weekday > 7:

weekday = weekday - 7

return weekday

def weekdays(ts):

return [weekday(t) for t in ts]

Compile it using easycython and then time it:

1

2

3

$ python test5.py

Function ` do_them ` took 0.03563655300240498 seconds to finish

Execution time was reduced from 0.30 to 0.036 seconds. Nice.

And faster

If a function’s return value is a simple C type, it can be beneficial to declare that as well.

1

2

3

4

5

# file 'version06.pyx'.

cdef long weekday(long ts):

# ... the rest is identical to file 'version05.pyx'

# ...

Note that we have replaced def by cdef in order to declare return type of the function.

Now time it:

1

2

3

$ python test6.py

Function ` do_them ` took 0.019489386002533138 seconds to finish

The execution time is further reduced from 0.036 to 0.019 seconds.

And faster

Let’s see whether Numpy can help us go further.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

# file 'version07.pyx'.

cimport numpy as np

cdef long weekday(long ts):

# ... identical to file 'version06.pyx'

# ...

def weekdays(np.ndarray[np.int64_t, ndim=1] ts):

return [weekday(t) for t in ts]

Compile it as before. The testing code becomes the following.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

# file 'test7.py'

import numpy as np

from pycc.version01 import verify

from pycc.profiler import timed

import pycc.version07 as mymod

@timed

def do_them(timestamps):

fn = mymod.weekdays

return fn(timestamps)

if __name__ == "__main__":

n = 1000000

timestamps = np.arange(n) * 1000

z = do_them(timestamps)

verify(timestamps, z)

Time it:

1

2

3

4

docker-user@pycctalk in ~/work/src/pycctalk

$ python test7.py

Function ` do_them ` took 0.06377661900478415 seconds to finish

Slower! How come?

Well, it’s known that accessing individual elements of a Numpy array is inefficient. (Numpy is great for vectorized operations.) Individual Numpy element access is happening repeatedly in weekdays. One idea is to turn those Numpy element accesses to C array element accesses. We’ll also take this opportunity to change the Numpy interface np.ndarray[np.int64_t, ndim=1] to the more elegant, and more general, memoryview interface (related to buffer protocol).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

# file 'version08.pyx'.

import numpy as np

cimport numpy as np

cdef long weekday(long ts):

# ... identical to 'version06.pyx'

def weekdays(long[:] ts):

cdef long n = len(ts)

cdef np.ndarray[np.int64_t, ndim=1] out = np.empty(n, np.int64)

cdef long[:] oout = memoryview(out)

cdef long i, t, z

for i in range(n):

t = ts[i]

z = weekday(t)

oout[i] = z

return out

Accordingly in the testing script, the line

1

z = do_them(timestamps)

is replaced by

1

z = do_them(memoryview(timestamps))

Compile as usual. Then time it:

1

2

3

4

docker-user@pycctalk in ~/work/src/pycctalk

$ python test8.py

Function ` do_them ` took 0.011735767999198288 seconds to finish

Another significant speed-up, from 0.019 to 0.012 seconds. This speed-up is achieved because a memoryview and a Numpy array exposes their data in a contiguous memory block, hence element access of them can be translated to element access into C arrays. Granted, this version is not strictly comparable with the baseline version due to the use of Numpy.

And faster

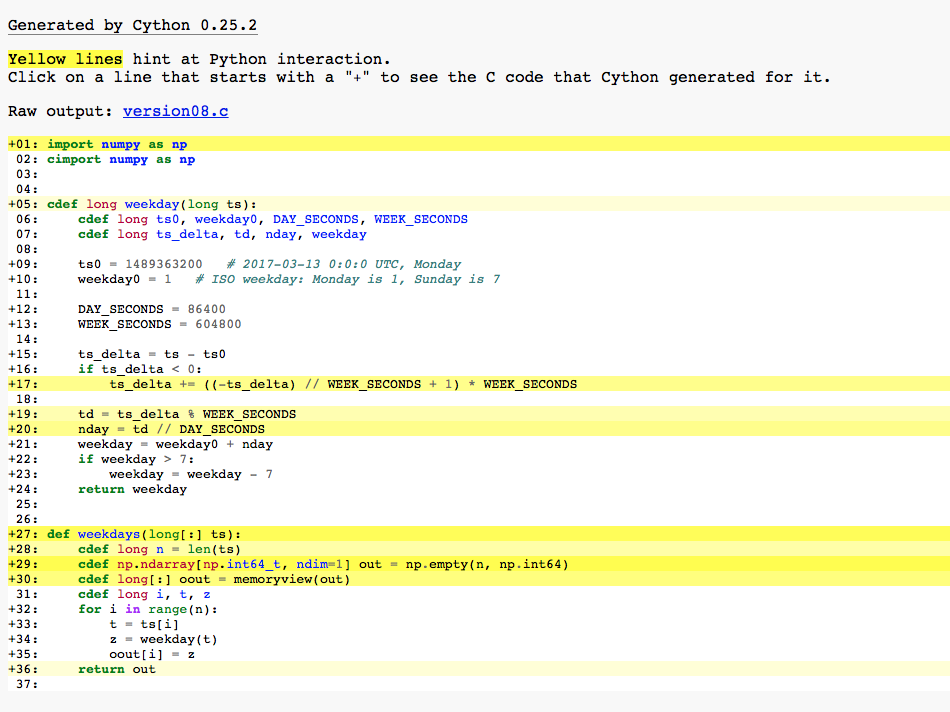

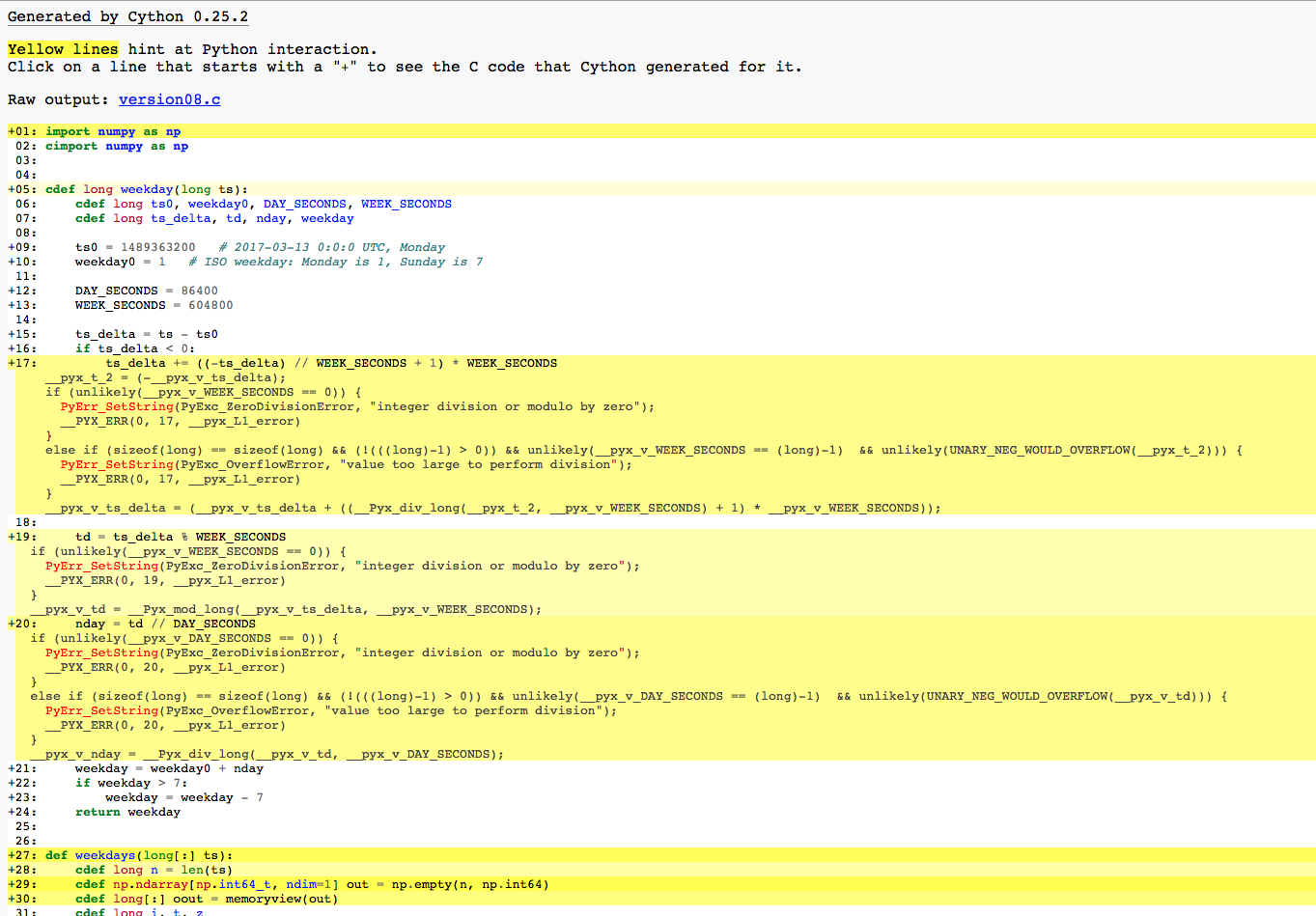

Besides version08.c, which is a C translation of version08.pyx, another file version08.html was generated for us. This file is useful for diagnostics during development. The content of this file is shown below.

The yellow-highlighted lines indicate Python, as opposed to C, operations. These are potential spots for speed tuning. Clicking on the yellow lines will show the corresponding C code translations.

In function weekday, we realize that the integer division and remainder functions // and % are Python functions. However, since the operands are all integers, we might use C functions of these operations for hopeful speed gain. This effect is achieved by the Cython decorator cdivision.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

# file 'version09.pyx'

import numpy as np

cimport numpy as np

cimport cython

@cython.cdivision(True)

cdef long weekday(long ts):

# ... identical to 'version08.pyx'

# ...

def weekdays(long[:] ts):

# ... identical to 'version08.pyx'

# ...

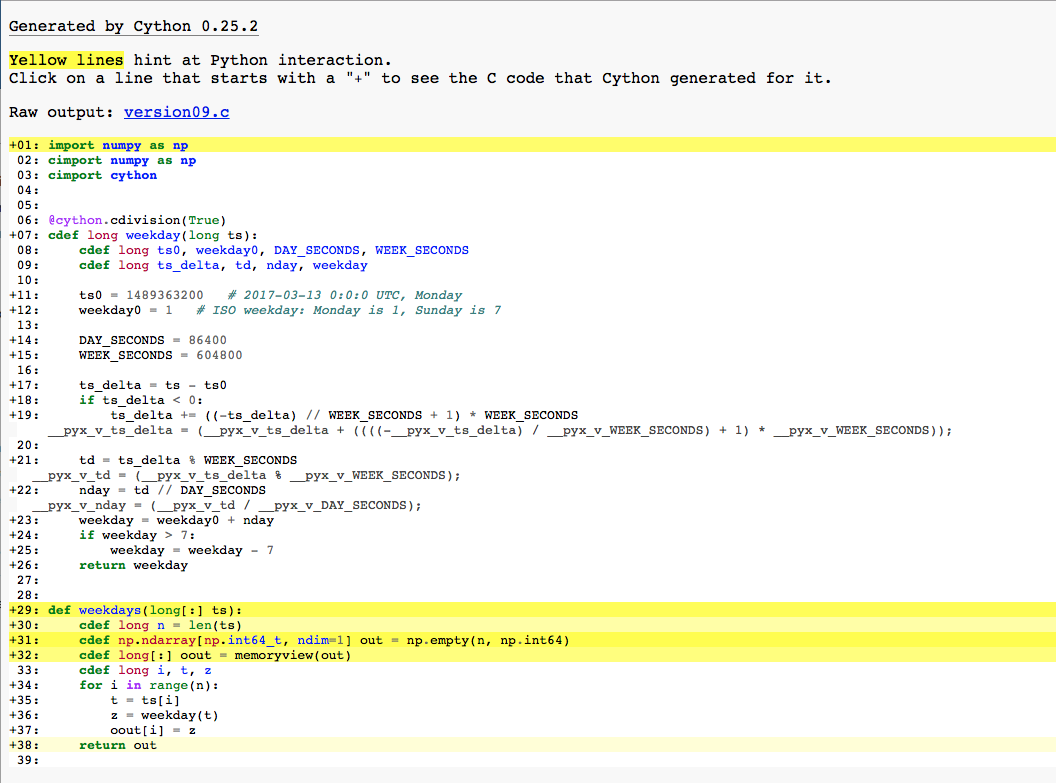

Let’s see the generated HTML file:

The yellow highlights in function weekday are gone. The previous yellow lines, which were translated to multiple lines of C code each, are now translated to a single line of C code each.

The function weekdays also has several yellow lines. Since they are outside of the big loop, we’ll not worry about them.

Now let’s see how it performs:

1

2

3

$ python test9.py

Function ` do_them ` took 0.005960473994491622 seconds to finish

Speed doubled from 0.012 to 0.006 seconds due to the one-line code addition for a decorator.

Use setup.py to compile

We have used easycython to compile the Cython source codes. This works fine for simple scenarios. For more complex and precise control, a setup.py file is the way to go. For the record, here is the setup.py file we can use for our case.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

# file 'setup.py'.

debug = False

from setuptools import setup, Extension

from Cython.Build import cythonize

import numpy

numpy_include_dir = numpy.get_include()

cy_options = {

'annotate': True,

'compiler_directives': {

'profile': debug,

'linetrace': debug,

'boundscheck': debug,

'wraparound': debug,

'initializedcheck': debug,

'language_level': 3,

},

}

extensions = [

Extension('version' + f, ['pycc/version' + f + '.pyx'],

include_dirs=[numpy_include_dir,],

define_macros=[('CYTHON_TRACE', '1' if debug else '0')],

extra_compile_args=['-O3'],

)

for f in ['05', '06', '07', '08', '09']

]

setup(

name='pycc',

version='0.1',

packages=['pycc',],

ext_package='pycc',

ext_modules=cythonize(extensions, **cy_options),

)

To compile using setup.py, do

1

$ python setup.py build_ext --inplace

Line-profile Cython code

Notice that setup.py contains a flag debug = False. If it is set to True, we can profile the Cython code to deep dive and identify potential bottlenecks. Let’s try it.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

# file 'version10.pyx'.

import numpy as np

cimport numpy as np

cimport cython

@cython.binding(True)

cpdef long weekday(long ts):

# ... identical to file 'version09.pyx'

# ...

@cython.binding(True)

def weekdays(long[:] ts):

# ... identical to file 'version09.pyx'

# ...

There are two changes in this code. First, the functions we intend to profile are decorated by cython.binding(True). Second, function weekday is changed from cdef to cpdef. The second change is needed to make weekday visible to Python. With cdef, the function is visible in the Cython file only.

Remember to set debug to True in setup.py, and then compile with

1

$ python setup.py build_ext --inplace

The testing script is changed to specify what functions to profile:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

# file 'test10.py'.

import numpy as np

from pycc.version01 import verify

from pycc.profiler import lineprofiled

import pycc.version10 as mymod

#@timed

@lineprofiled(mymod.weekday, mymod.weekdays)

def do_them(timestamps):

fn = mymod.weekdays

return fn(timestamps)

if __name__ == "__main__":

n = 1000000

timestamps = np.arange(n) * 1000

z = do_them(memoryview(timestamps))

verify(timestamps, z)

lineprofiled is a decorator that specifies the functions to line-profile.

Now that Cython is compiled and profiling is set up, let’s see it at work:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

$ python test10.py

Timer unit: 1e-06 s

Total time: 38.9864 s

File: /home/docker-user/work/src/pycctalk/pycc/version10.pyx

Function: weekday at line 8

Line # Hits Time Per Hit % Time Line Contents

==============================================================

8 cpdef long weekday(long ts):

9 cdef long ts0, weekday0, DAY_SECONDS, WEEK_SECONDS

10 cdef long ts_delta, td, nday, weekday

11

12 1000000 3276262 3.3 8.4 ts0 = 1489363200 # 2017-03-13 0:0:0 UTC, Monday

13 1000000 3245958 3.2 8.3 weekday0 = 1 # ISO weekday: Monday is 1, Sunday is 7

14

15 1000000 3248079 3.2 8.3 DAY_SECONDS = 86400

16 1000000 3249707 3.2 8.3 WEEK_SECONDS = 604800

17

18 1000000 3251594 3.3 8.3 ts_delta = ts - ts0

19 1000000 3246934 3.2 8.3 if ts_delta < 0:

20 1000000 3245771 3.2 8.3 ts_delta += ((-ts_delta) // WEEK_SECONDS + 1) * WEEK_SECONDS

21

22 1000000 3244921 3.2 8.3 td = ts_delta % WEEK_SECONDS

23 1000000 3243649 3.2 8.3 nday = td // DAY_SECONDS

24 1000000 3243234 3.2 8.3 weekday = weekday0 + nday

25 1000000 3242299 3.2 8.3 if weekday > 7:

26 weekday = weekday - 7

27 1000000 3247993 3.2 8.3 return weekday

28

29

30 @cython.binding(True)

31 def weekdays(long[:] ts):

32 cdef long n = len(ts)

33 cdef np.ndarray[np.int64_t, ndim=1] out = np.empty(n, np.int64)

34 cdef long[:] oout = memoryview(out)

35 cdef long i, t, z

36 for i in range(n):

37 t = ts[i]

38 z = weekday(t)

39 oout[i] = z

40 return out

Total time: 89.7384 s

File: /home/docker-user/work/src/pycctalk/pycc/version10.pyx

Function: weekdays at line 31

Line # Hits Time Per Hit % Time Line Contents

==============================================================

31 def weekdays(long[:] ts):

32 1 20 20.0 0.0 cdef long n = len(ts)

33 1 27 27.0 0.0 cdef np.ndarray[np.int64_t, ndim=1] out = np.empty(n, np.int64)

34 1 21 21.0 0.0 cdef long[:] oout = memoryview(out)

35 cdef long i, t, z

36 1 4 4.0 0.0 for i in range(n):

37 1000000 3321506 3.3 3.7 t = ts[i]

38 1000000 83089403 83.1 92.6 z = weekday(t)

39 1000000 3327384 3.3 3.7 oout[i] = z

40 1 12 12.0 0.0 return out

The line profiling reveals no clear bottleneck, suggesting that we are probably close to the limit of what we can do. After all, weekday is now a simple function in C.

Epilogue

So, with some basic use of Cython (and a little bit of Numpy), we reduced the execution time of a piece of short, innocent-looking Python code from 0.88 seconds to 0.006 seconds. That’s a 147X speed-up. If the baseline version needs 24 hours to run, the optimized version will be done in 10 minutes.

Now, if you are thinking, “Wow! So much room for speed improvement! Too bad you started in Python!”, you would be missing the point.

Let me stress that the first version of 3-line pure Python code is clean and clear. It is absolutely the right place to start. In real-world projects, such a function is most likely not a speed bottleneck. We should not sweat over Python’s speed anywhere except at quantitatively identified bottlenecks, and those are necessarily small chunks of code. Everywhere else, enjoy the elegant, productive language and vast ecosystem that Python offers.

Any improvements made anywhere besides the bottleneck are an illusion. — Gene Kim

Cython appears to be in good health: the project has been under consistently active development since 2007, and is being used by heavy-weight projects including Numpy, pandas, scikit-learn, SciPy, and Appache Arrow.

If nothing else, Cython has considerably boosted my confidence in starting a project in Python, knowing that there is a way to speed it up if that time comes, at all.